This week in history features George Washington and his feats before the American Revolution.

A continent up for grabs

By the middle of the 18th century the entire continent of North America was still up for grabs – the board lay open, waiting for each party to make its move.

The French had strongholds in Louisiana and to the north along the Mississippi River. They had a firm hold over Montreal and the region of Quebec and now looked to complete the chain of forts and settlements into the Ohio River Valley, joining their northern holdings with their southern ones in the Gulf.

The English, fearful of the stranglehold this would place on their colonies – essentially preventing them from expanding west of the Appalachians – looked to stop their centuries-long enemies from accomplishing this maneuver.

This geopolitical tango dance guaranteed the conflict that was to come: the French and Indian War, just one theater of the larger Seven Years War that waged across Europe (read more about the lead-up to the war in this previous “This Week in History” article).

This geopolitical tango dance guaranteed the conflict that was to come: the French and Indian War, just one theater of the larger Seven Years War that waged across Europe (read more about the lead-up to the war in this previous “This Week in History” article).

Although war would not officially be declared until 1756, beginning in 1754 the two empires clashed in a series of bloody conflicts that swept into its stream many of the same people who would feature prominently in America’s future War of Independence: Horatio Gates, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington among thousands of others.

Washington’s first taste of war

In December of 1752 George Washington, a young Virginian gentleman-farmer who had just come into possession of his half-brother’s estate on Mount Vernon, was made a commander of Virginia’s militia.

Although he had no previous military experience, that wasn’t unheard of in the colonies. The position was, after all, as much political as military.

Fate, however, saw fit to place Washington in the position precisely when things started heating up. The French-backed Indians continued to raid the colony’s eastern borders, and the colonial assembly was inundated with the cries from refugees fleeing the conflict. Something had to be done.

First, diplomacy. In 1753, Lieutenant Governor of Virginia Robert Dinwiddie sent 21-year old Washington to the French to demand they halt their harassment of traders in the Ohio-River valley.

Although he returned with bad news – the French had no such intentions – Washington published his account of his journey through what was largely-unexplored territory; an account that made the dashing young officer an instant celebrity.

A year later, Dinwiddie ordered now promoted Lieutenant-Colonel Washington take 160 Virginia militiamen and return to the Ohio country to “act on the defensive” but, if faced with resistance “make Prisoners of or kill and destroy” all those who got in his way.

On his way to the region at the head of a reconnaissance party, Washington ran into the French diplomatic-military delegation on a similar mission to Washington.

Shots rang out and after a brief firefight the officer in charge of the French company, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville and over a dozen other Frenchmen lay dead. Washington’s brief foray and firefight ignited the brewing conflict into open war.

The coming of Braddock

With war inevitable, the British sent Major General Edward Braddock and a small number of regular troops to her colonies in the New World.

Upon arrival to his new command, he immediately set about concocting a plan to deal with the French. The half-hearted attempt at diplomacy hadn’t been working and Washington’s brief foray against them confirmed what the British had already assumed: the French would continue chipping away at the fragile borders of the English colonies.

Military might would be Braddock’s plan; a four-pronged assault that would finally check French aggression.

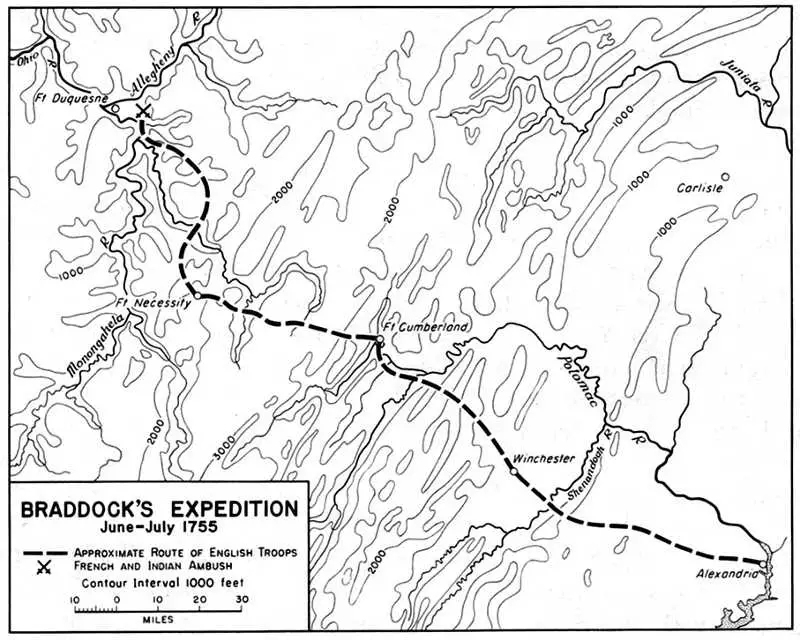

Braddock himself would lead the prong against Fort Duquesne, a stronghold the French had used to lead raids against Pennsylvania and Virginia.

The fort itself sat in what is today downtown Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Braddock would lead more than 2,000 regular troops and an assortment of colonial militia and Indian allies on this assault through dense, nearly impenetrable wilderness.

Before he could set off however, Braddock faced a logistical nightmare unequaled in European theaters of war: miles upon miles of virgin forest with no more than animal trails piercing its veil.

Braddock had to muster colonial support for such an enterprise. Unfortunately, the British general was not all around well-liked by the Americans he frequently insulted.

Benjamin Franklin, who had the dubious honor of hosting the general on his way to his ill-fated battle against the French commented on Braddock: “The General was, I think, a brave man, and might probably have made a good figure in some European war. But he had too much self-confidence; too high an opinion of the validity of regular troops; too mean a one of both Americans and Indians.”

There was one American the general took rather well to: George Washington. Rather than maintain his low militia rank, Washington had tried but failed to obtain a commission in the British army. Instead, he served as a volunteer aide-de-camp to Braddock, who took the young officer on willingly.

After gathering as many wagons and other supplies as he could harangue from the colonials, Braddock set off with his men on an extremely ill-conceived campaign in Spring of 1755. Rather than start the march to Fort Duquesne in Philadelphia, Braddock set off from Virginia – a route that added many miles over the rugged hillsides of the Allegheny Mountains.

Leading the column of soldiers, which often stretched like a massive snake four miles behind, were a troop of brawny men wielding axes. These woodsmen cut a broad path through the forest, opening the way for the army (complete with cannon) to follow behind.

Salvage from defeat

Reaching the River Monongahela on this day in 1755, the advance force of Braddock’s army, some 1,300 strong, were surprised by a much smaller force of French and Indians who had set out from Fort Duquesne to reconnoiter the British.

Taking advantage of the cover, the French sniped at the British troops. The very road they had cut through the forest now served only to expose the British to the ruthless musketry of their unseen enemies.

Although many officers attempted to organize the soldiers into some semblance of order, too many of their number fell to well-placed shots from the tree line (out of the 86 officers under Braddock well over 50 of them were either killed or wounded during the fight).

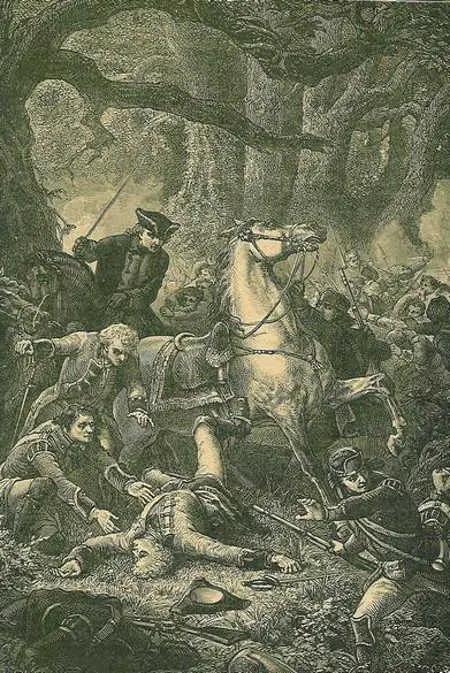

Among the number of British officers fatally struck down was Braddock himself. With panic in the air, George Washington rode out.

Temporarily suffering from one of the many illnesses that cloud about armies of the day, Washington had been lagging behind when the fighting started. Now the tall Virginian rode pell-mell to the line of battle and attempted to organize some semblance of order in the retreating troops.

Over the course of the next several hours, the 23-year old Washington had two horses shot from under him and his jacket riddled with bullet holes.

All in all, the British had some 977 killed or wounded in what turned out to be a smashing defeat in a war that was not even officially recognized yet.

From the ashes of defeat, however, arose the name of the young George Washington, proclaimed by some “the Hero of Monongahela.”

Antone Pierucci is a Sacramento-based public historian and a freelance writer whose work has been featured in such magazines as Archaeology and Wild West as well as regional California newspapers.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?