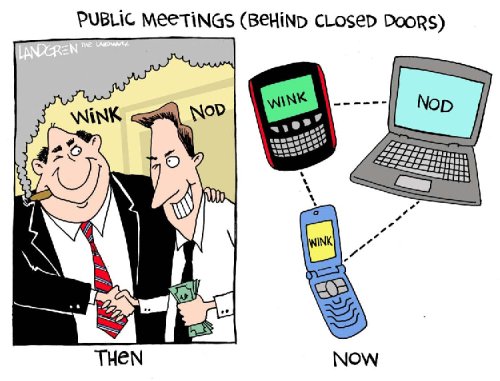

March 16-22 is Sunshine Week, the time to discuss and explore the concept of open government. The following column, provided by Sunshineweek.org, in one of a series Lake County News will offer this week as part of the important discussion of keeping government information available to the public.

Freedom of information laws differ from one state to another, and now, from one country another. But there are likely similarities among them that enable us to offer a few general observations.

I deal with the New York Freedom of Information Law (known widely here as "FOIL"), and I'm troubled by a variety of common beliefs that have grown into myths which simply are not true. The problem in part is that many Americans tend to follow like sheep, and when we hear the same kind of comments over and over again, too many of us begin to believe them. One of my continuing goals involves waking up the public, government officials, and yes, even reporters, and trying to ensure that they avoid falling into the traps created by myths relating to government’s ability to keep secrets.

Although my experience involves the law in New York, my guess is that much of the following would apply in a variety of jurisdictions.

Myth: Characterizing a record as "draft," a "work in progress" or "unofficial" enables a government agency to automatically deny access to the record.

Reality: FOIL pertains to all government agency records and defines the term "record" to include any information, in any physical form whatsoever, kept, held, filed, produced or reproduced by with or for a government agency. Often drafts or works in progress include statistical and factual information that is available to the public. When a record comes into the possession of an agency, whether it is deemed "official" or "accepted" is irrelevant; it is subject to rights conferred by FOIL. Also, minutes of meetings must be made available, even if they haven’t been approved.

Myth: Stamping or marking a record "confidential" enables the government to withhold it.

Reality: Under the New York FOIL, marking or agreeing to keep a record "confidential" is meaningless. In brief, FOIL says that all government records are accessible, unless the records may be withheld based on a series of exceptions to rights of access listed in the law. The law determines what's public and what's not, not an agreement or claim of confidentiality.

Myth: Personnel records are confidential and discussions involving personnel matters can be discussed in closed or "executive" sessions of government bodies.

Reality: The word "personnel" cannot be found in either the FOIL or the Open Meetings Law. Although some aspects of personnel records pertaining to government officers or employees may be withheld, others are accessible under FOIL, particularly those that relate to their duties, such as salary, overtime, attendance, disciplinary action, etc. Similarly, personnel matters involving policy or the allocation of public money (i.e., whether to create or eliminate a position) must be discussed in public. Only when an issue focuses on a particular person in relation to one or more among a series of qualifiers (i.e., a discussion of a specific individual's performance) would there be a basis for going into a closed session to discuss a personnel matter.

Myth: Records involving litigation are confidential and government officials cannot discuss litigation.

Reality: When records are submitted to a court because a lawsuit has been initiated, the records are generally available from the court. With respect to meetings of government bodies, the courts have held that a closed meeting may be held by those bodies to discuss their litigation strategy in private, so as not to divulge their strategy to their adversaries. They have also held, however, that the mere threat, the fear or the possibility of litigation is not enough to justify holding a closed meeting.

Myth: When an incident is under investigation, law enforcement officials cannot disclose anything about it.

Reality: There is nothing that precludes those officials from speaking, and they do when there may be an advantage. Further, FOIL usually requires that a variety of details relating to the incident be made public, unless disclosure would interfere with an investigation or deprive a person of a right to a fair trial, for example.

Remember: When you hear or read statements from a government officials indicating that the matter can’t be disclosed because it's a personnel matter, it's in litigation, it's under investigation, or because it's confidential, often what they're really saying is that they don't want to disclose, even though they can or, in some circumstances, they must.

Freeman is Executive Director of the New York State Committee on Open Government in Albany.

{mos_sb_discuss:4}