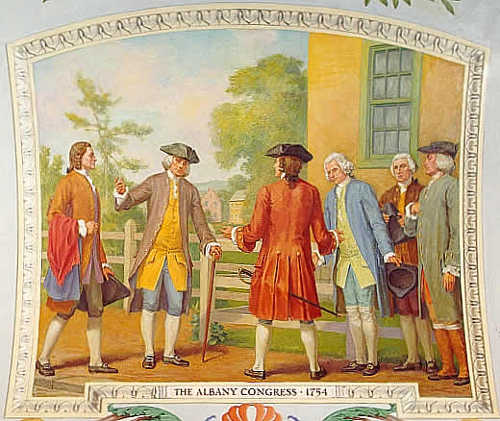

This week in history takes a look at the proposal that likely would have delayed, if not prevented the American Revolution: the Albany Congress of 1754.

June 19, 1754

No single episode in our nation’s history is more idealized than the revolution that created it, and rightfully so, to some extent.

Hindsight reveals a remarkable list of instances when the outcome of the struggle could have – indeed should have if you were a gambling person – gone differently.

The number of narrow escapes George Washington achieved throughout the war alone is beyond the pale. His army should have been crushed more times than not and yet time and again he escaped with a sufficiently large force to prolong the war until eventual success.

Those religiously inclined among us see the providential hand of God in these seemingly random acts of luck. Books have even been written on the subject (I’m thinking in particular of “America’s Providential History” by Stephen McDowell and Mark Beliles).

However you choose to explain them to yourself, there is no denying that the near-misses and small turns of fate played a major role in America’s success.

If we were to expand our lens outwards, beyond the confines of the war itself, we would actually see that these twists of luck happened well before hostilities even began.

An important event that, in hindsight, can be added to the list of providential (or lucky) turns for our country actually happened a quarter century before the Declaration of Independence. I’m thinking of the 1754 Albany Congress.

The backdrop to the Albany Congress was the growing tension between the French and British colonies in North America.

By the early 1750s the British colonies were increasingly threatened by the French-backed Indians and their raiding parties.

War between England and France had not yet officially broken out, but in North America there was no doubt that something would have to be done to curb the deteriorating relationship between the colonists and the neighboring Indian tribes to the west – and no reconciliation could be achieved so long as the French continued to incite the Indians to violence.

You see, by the middle of that century, the entire continent of North America was still up for grabs – the board lay open, waiting for each party to make its move.

By the 1750s the French had strongholds in Louisiana and to the north along the Mississippi River. They had a firm hold over Montreal and the region of Quebec and now looked to complete the chain of forts and settlements into the Ohio River Valley, joining their northern holdings with their southern ones in the Gulf.

The English, fearful of the stranglehold this would place on their colonies – essentially preventing them from expanding west of the Appalachians – looked to stop the French from accomplishing this maneuver.

This, in addition to the centuries-long animosity between the two kingdoms, guaranteed the conflict that was to come: the French and Indian War, just one theater of the larger Seven Years War.

The ensuing conflict would pit for the first significant time the resources of the colonies against another nation, a prelude to the Revolutionary War.

Operating nearly autonomously from each other, the British colonies had struggled to adequately address the increasing hostility of the French and their native allies.

To make matters more complicated, the colonists were proud of their individuality. It was to “King and Colony” as much as “King and Country” that each colonist toasted heartily.

As hostilities increased on the continent, some colonial leaders recognized that the very object of their pride would be their downfall should the small territorial conflict flare up into open war.

It would be easy for the French (and later the British) to divide the colonies and conquer them piecemeal.

Although definitely to a lesser extent, the same sentiment was felt back in London and so in June of 1754 a meeting was called in Albany, New York for representatives of 7 of the 13 colonies.

The central object of the meeting was actually just to renew negotiations between the northeast colonies and the strategically important Mohawk Nation, a tribe of natives who were part of the larger Iroquois Confederation.

But the ulterior motive behind convening the meeting was to bring these colonies together to foster inter-colonial cooperation.

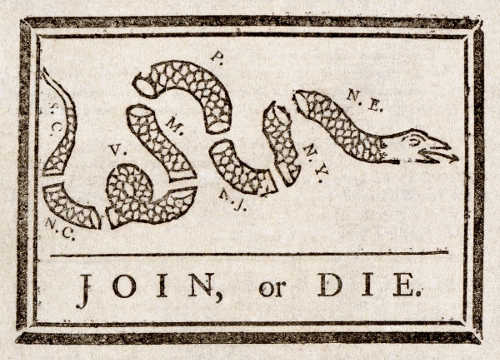

At the head of the Albany Congress was a Pennsylvanian man named Benjamin Franklin. Having started his career as a newspaperman, Franklin was quick to recognize the importance of currying public opinion, a tactic that would later prove vital in starting the Revolution.

In order to drum up support for the meeting and to highlight the imperative nature of cooperation, he designed a now-famous cartoon: the image of a snake, divided into parts, each labelled with the abbreviation for the individual colonies and, below, the words “Join or Die.”

On this day in 1754 the Albany Congress convened for the first time. By June 18, having discussed the matter of the Mohawks, all commissioners voted to convene again to discuss a proposal for creating a more centralized governing structure among the colonies.

They created a committee, with Franklin playing a major role, and it submitted a draft Plan for Union on June 28.

After several days of arguments and several drafts later, the committee approved the Albany Plan for Union on July 10.

The plan stipulated the following: the colonial governments of all but Delaware and Georgia were to select members to a “Grand Council,” while the British would select a “President General” to preside over the council; together these two branches of government would regulate colonial-Indian relations and resolve any territorial disputes.

Despite passing the Congress itself, both the colonies themselves and the British proved too stubborn for the proposal to take effect.

The colonies didn’t want any curbing of their power over their own territory and the British believed that directives from London were sufficient to govern.

In essence, the proposal had attempted to reconcile the colonies’ growing desire to reform colonial-imperial relations with England’s own desire to keep her colonies in their place in the hierarchy of Empire (hence the President General would be selected directly by London).

We sometimes forget that right up until the height of the hostilities between Great Britain and her former colonies, those same colonists proudly proclaimed themselves British subjects.

The Albany Plan was very much a middle-of-the-road proposal that would have kept both parties happy – at least for a while.

In the end, the failure of the proposal made the future War for Independence far more likely than it had been before. It ensured that the colonies would remain far subordinate to the dictates of London, a tyrannical rule of law that would eventually drive many of the same men who proposed the Albany Plan to develop a far more radical form of government – one of self-rule.

For men like Benjamin Franklin, the process of devising a form of government where individual, semi-autonomous colonies were controlled by centralized branches of power would be good practice for the decades ahead.

Antone Pierucci is the former curator of the Lake County Museum in Lake County, Calif., and a freelance writer whose work has been featured in such magazines as Archaeology and Wild West as well as regional California newspapers.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?