I see and hear a great many things about wetland restoration. Can you tell me why so much importance is put on restoring wetlands and how it's done?

Thanks!

-Wondering about Wetlands from Witter Springs

Dear Wondering,

Thanks for this question! You are right that “wetland restoration” is a popular term right now and you probably are reading and hearing about it all over, especially in Lake County. Sometimes wetlands get overshadowed and are underappreciated in comparison to lakes, reservoirs, streams, and creeks. However, wetlands play one of the most important roles in both aquatic ecosystems and terrestrial ecosystems.

Wetlands represent zones of transition between typical terrestrial ecosystems and aquatic habitats such as lakes and seas. These zones of transition are called ecotones. One reason why wetlands are overshadowed and underappreciated is because they are difficult to work with and live in. They are not always aquatic and not always dry. They are not as easy to categorize as lakes, streams and oceans.

More recently, the true importance of wetlands has become fully realized. Did you know that wetlands are one of the only ecosystem categories protected by the U.S. government? It’s true. Protection is regulated both indirectly and directly by the Clean Water Act. Wetlands are protected globally too. In 1971, the Ramsar Convention resulted in a treaty establishing the protection of important wetlands across the globe.

Defining and recognizing a wetland

The Ramsar Convention defines wetlands as, “ a wide variety of natural and human-made habitat types ranging from rivers to coral reefs… Wetlands include swamps, marshes, billabongs, lakes, salt marshes, mudflats, mangroves, coral reefs, fens, peat bogs, or bodies of water - whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary.

Water within these areas can be static or flowing; fresh, brackish or saline; and can include inland rivers and coastal or marine water to a depth of six meters at low tide. There are even underground wetlands.”

Think about this definition. Does it describe anywhere in Lake County you can think of?

The water that creates wetlands comes from a variety of sources, such as precipitation, runoff from the surrounding landscape, nearby streams or lakes, and even seepage from the ground itself, from ground water or springs. The many sources of water into a wetland make it difficult to distinguish a wetland solely based on the presence of standing water.

That explains why in 1987, the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) created a wetland delineation manual that included field-based indicators such as soils, vegetation, and hydrology. The process of wetland delineation is simply being able to draw a line or border around a wetland, so that protections can be implemented when building or land alteration is to take place.

It is confusing however, for a wetland to be delineated as a wetland when in fact it does not necessarily contain standing water. A wetland might in fact never be covered in standing water, but it’s plant’s roots and surrounding soils may be effectively wet, frequently wet or soaked for a given amount of time, even without visible, standing surface water.

Wetlands are susceptible to events that can have negative impacts for both terrestrial and aquatic environments. Flooding can bring in water, but also excess nutrients, sediments, contaminants and even sometimes invasive species. Wave energy and flood pulses can uproot plants and flush out needed nutrients or smaller, sensitive organisms, seeds, and propagules.

Wetlands are variable, and this makes it difficult for most organisms to live among a wetland. The constant change in conditions, from inundation and flooding, to prolonged dry periods, can pose challenges and unique environments to organisms.

Therefore wetlands need our protection, because the organisms and vegetation that is found living - thriving - in wetlands is accustomed to that highly variable environment, and not many other places outside of a wetland.

Importance of wetlands

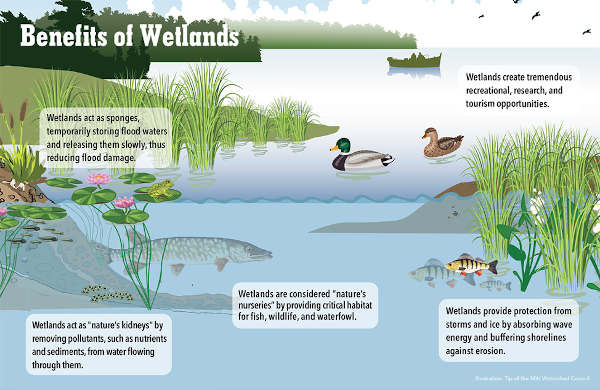

I already mentioned the importance for protecting wetlands due to the flora and fauna that are found in that ecosystem. However, wetlands serve other important roles that have local, regional and even global benefits.

The majority of wetlands are by nature “wet.” Therefore most of the material that flows or falls into a wetland is submerged in water or wet soils and other vegetation. This submergence slows decompositional processes. This is mostly due to the continued aquatic state of a wetland, where oxygen is limited, slowing down the metabolic processes that occur during decomposition. Basically this means that materials, mostly carbon-containing organic materials, can remain “trapped” in wetlands for very, very long periods of time. Sometimes for a millenia.

If combating climate change is of interest and a priority for you, then conservation, restoration, and recreation of wetlands would be at the top of your list. This is because wetlands are a huge carbon sink - meaning they store large amounts of carbon that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey’s Woods Hole Coastal and Marine Science Center, the wetlands within the continental US can hold at least 3.2 billion metric tons of C02 or equivalent. This equates to about half of the US’s net total greenhouse gas emissions in the year 2019 alone.

Wetlands can store carbon in several ways, the main one being through aquatic vegetation production. Plants take in C02, and release oxygen. Wetlands contain dense and abundant vegetation. The plants take in C02 from the atmosphere and use the carbon to grow- the structure of plant cell walls is mostly made of polysaccharides (i.e. cellulose), which is majorly made up of carbon atoms (and some oxygens and hydrogens of course!).

Even when the plants die, the tissue degrades, but those long polysaccharide chains fall away into the rest of the wetland, being broken down and consumed by organisms such as insects, fungus, and bacteria. The basic building blocks of this decomposition process remain within the wetland environment - feeding other plants and organisms.

If a living thriving wetland can store carbon, then the deconstruction and draining of wetlands, say for the conversion into agriculture lands or development, can release that carbon. And the impact is more drastic than that initial release. If a wetland is destroyed, future carbon storage is no longer occurring, and that benefit can be lost forever. Unless the wetland can be restored anew.

In addition to the carbon storage capabilities of wetlands, there are some economic benefits to wetlands. For example, along coastlines and shorelines, the presence of a healthy wetland can serve as a buffer, or safety line, against storm surges and floods, which are more frequent now thanks to climate change. Buffer strips of natural shorelines (mini wetlands) can reduce shoreline erosion and structure damage during large wave events, and prevent scour that can undermine the integrity of sea walls, shoreline structures, and docks.

Wetland plants and organisms, and mostly microorganisms, can serve as filters for excess nutrients and pollutants. Wetlands around Clear Lake for example, reduce shoreline and stream inflow erosion, and the physical and chemical processes in wetlands filter out troublesome nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen, which are the major food source to algae and the sometimes toxic cyanobacteria.

Clear Lake is estimated to have lost about 85% of her shoreline wetlands, including the large northern wetland of Robinson Lake (now located within the current Middle Creek Marsh Restoration Project boundary). Prior to shoreline development and wetland conversion, Clear Lake, although a very productive lake from hundreds of thousands of years of inputs, probably had a more robust wetland filter surrounding her shores. This wetland buffer was essential in mediating large storm influxes, floods, and drought events, as well as providing a vital food source for the lake’s biodiverse plant, animal - and human -communities.

How do we save our wetlands?

Once we learn how important wetlands are, and how many acres have been destroyed, displaced, or altered, the next question, as you pointed out Wittier Springs, is how we can save and restore wetlands.

Before we jump into methods to save wetlands, let’s talk about one more important thing that wetlands provide and an example of that concept being regionally utilized to restore wetland environments.

Wetlands are a hotbed of biodiversity. Wetlands provide habitat and breeding grounds for a wide variety of wildlife, from fish, to birds, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Wetlands provide vital food sources, such as plants, seeds, algae, zooplankton, and invertebrates — not just within the wetland itself, but these resources “leak” out into adjoining streams and lakes, providing a stable and nutritious food source for the majority of aquatic and some terrestrial organisms.

This concept is being used in floodplain wetland recreation within the Central Valley to save the Chinook Salmon. Historic floodplain areas, long having been cut-off from rivers, converted and used for agriculture, are now being re-flooded, and used as “temporary wetlands” to create the valuable food sources that flush downstream to juvenile and growing salmonids.

This program is vast, but one of the major proponents and contributors is Trout California, with a program called Fish Food on Floodplain Farm Fields (See? I am not the only one who uses alliteration as a fun way to learn and embrace aquatic science!). This Fish Food program has one major goal: to harness the benefit of wetlands to help solve the salmon population decline problem in the Sacramento Valley in California.

This temporary wetland re-creation was so successful in the Sacramento Valley, that the California Department of Water Resources re-created it in the Delta to boost food sources for Delta smelt. That research is ongoing, but so far results indicate that this strategy does provide additional food sources for fish and this innovative strategy might go a long way to save the smelt and other vulnerable fish species living in estuarine systems. If you want to learn more about that project, you can visit this peer-reviewed published, open-access article by Frantzich et al. (2021).

So how can all this help the wetlands around Clear Lake? Well, while Clear Lake doesn’t have salmon, there are several other important native fish species that depend on robust wetland ecosystems to provide vital food resources, shelter, refuge, and safe breeding grounds.

For example, one species is the Clear Lake Hitch, an endemic minnow species found only in Clear Lake. You can learn more about the Hitch in my previous column from January 16, 2021. You can find that article, and a very useful video, here.

Hitch numbers are declining, significantly, in the Clear Lake ecosystem. The exact answer to why that is is mostly unknown at this time. Although based on conversations with biologists from California Department of Fish and Wildlife and United States Geological Survey, lack of available and suitable habitat and food sources in the streams, shorelines, and wetlands of Clear Lake, is the most likely culprit.

Therefore, the restoration of wetlands around Clear Lake will have multiple benefits, to people, animals, and fish, including the state-threatened Hitch.

Generally, wetlands restoration projects take a long time and are complicated. Usually , but not always, the area of land containing a beneficial wetland, or the location best suited for wetland restoration, is owned by a private company or individual. Usually, the first step is acquisition, purchase or transfer of the private property into a conservation easement.

A conservation easement, according to the National Conservation Easement Database, is defined as a voluntary, legal agreement that permanently limits uses of the land in order to protect its conservation values. Also known as a conservation restriction or conservation agreement, a conservation easement is one option to protect a property for future generations.

Usually an public agency or non-profit organization, that purchases the easement, is responsible for managing the land for net ecosystem benefit, meaning restoring it to it’s maximum environmental purpose or value. This could include removing structures and buildings, removing invasive species or non-native vegetation and animals, planting native plants, modifying previously hydromodified water channels or shorelines.

About five years ago, I worked for a non-profit in Southern California, and our job as field scientists and technicians every day was basically to plant, monitor, water, and remove invasive weeds from the land that we had acquired. All of these activities were essential in restoring the landscape to its native state.

Properties under conservation easements do not necessarily have to be accessible or usable by the public, although many are because that is an important way to get further community support, funding, volunteer in-kind labor, and community involvement for future projects that improve the easement.

Conservation easements or agreements do come with some rules. They can never be developed, and while the original owner(s) do still have some access and use rights, their activities are restricted to those deemed to cause minimal or low impact. Excluded activities might include grazing, growing crops, water pumping or drilling, camping, off-road vehicle use, commercial use, or tourism use.

Not all restoration properties are conservation easements. Some may be gifted as donations, or purchased outright as part of a larger project.

Once a property is purchased, or made into a conservation easement, the next step is conducting full inventories and accounting of the property. Some questions a restoration or project manager might ask would be: What is there? What do we need to keep? What needs to be removed? What physical modifications need to be made to create the space into the benefit it was intended for?

For wetlands, this usually means removing physical barriers that disconnected the historic wetland space from the desired connecting water bodies, such as creeks, streams, lakes, estuaries, or oceans. Next will be a determination if the site needs simplified conservation and management, or larger, more complicated restoration.

Conservation or management could include some vegetation or animal management like hunting, trapping, re-introductions and maintenance of native or keystone species. Usually all wetland projects involve some level of invasive species management and control, and this effort never really stops, as invasives are stubborn, are hard to get rid of, and can constantly be reintroduced into space and outcompete native species communities.

More complicated restoration work could include sediment removal or earthmoving, such as the demolition of structures, removal or destruction of levees, dikes, or berns. Some wetland restorations require the removal or dismantling of a weir, channel, or dam, to allow water to flow back into the historic wetland area, or allow the area to reflood during the storm season.

Usually every step of conservation and restoration involves additional funding and expensive expertise. Agencies and non-profits usually acquire needed funding for each step, and leverage the completed steps and progress to acquire additional funds and resources. A significantly large portion of the funds that provide for wetland acquisition and restoration comes from state and federal governments in the form of grants, with some contributions from the private sector, foundations, or individual donations.

The rationale for wetland conservation and restoration investment coincides with the idea, correctly being, that the restored wetland will provide a comprehensive benefit to all people, plants, and animals, now and into the future.

Wetland restoration efforts Around Clear Lake

There are current efforts to restore wetland spaces around the shorelines and streams of Clear Lake. Some projects are fairly small (less than an acre) and some are relatively large (40 acres or more!). Some projects don’t look like much but they are vital to the retention and preservation of wetlands within the shoreline of the Lake.

I list a few of the projects below, however there are many more that I don’t cover in this list. In reality, every wetland project deserves it’s own dedicated Lady of the Lake column, and they might be covered individually, and in more detail, later in the year, so keep an eye out!

Where applicable, I provide project websites or contact information, just in case you, or someone you know, wants to help support, or be involved in these beneficial wetland restoration efforts.

1. The Middle Creek Flood Damage Reduction and Ecosystem Restoration Project. This project will restore the former Robinson Lake and Middle Creek Wetland and is organized by the Lake County Watershed Protection District with partners and funds from the US Army Corps, Department of Water Resources, County of Lake, Middle Creek Restoration Coalition, Robinson Rancheria, and Blue Ribbon Committee for the Restoration of Clear Lake.

According to the project website, this project will eliminate “flood risk to 18 residential structures, numerous outbuildings and approximately 1,650 acres of agricultural land and will restore damaged habitat and the water quality of the Clear Lake watershed. Reconnection of this large, previously reclaimed area, as a functional wetland is anticipated to have a significant effect on the watershed health and the water quality of Clear Lake”

The 1,650 acres of restored wetlands will create valuable space for wetland plants and dependent animals to flourish and provide valuable habitat and food resources for fish and animals living among the adjacent streams and Clear Lake.

This project has monthly meetings open to the public. If you would like to participate or be informed of activities and progress with this committee, please visit the project website here.

2. The Lake County Land Trust Wright Property Acquisition and Wetland Reconnection Project. In 2019, the Lake County Land Trust (LCLT) received a grant from the California Prop 1 Wildlife Conservation Board and along with many generous donations from the Lake County community and citizens, the LCLT was able to purchase the 200-acre parcel located in the south Lakeport area within the Big Valley Wetlands Project zone.

This purchase, and the promise of wetland protection, is great news for Clear Lake. The Wright Property is really the epitome of a prime ecotone wetland habitat, connecting the aquatic zone, and it’s inhabitants, to terrestrial ecosystems.

According to the LCLT Wright Property Easement webpage, “The Wright Wetland Preserve is as close to the original, natural shoreline as you can get. It's also home to black-tailed deer, California quail, wild turkey, raptors, waterfowl such as white pelicans, black bass, catfish, otter, mink, as well as habitats that support special status species including Clear Lake hitch and western pond turtle. Habitats found on this property range from lake to freshwater marsh, and from pasture to valley oak woodland.”

The next phase of this project involves removing a levee-berm that has been in place for about 50 years. Once this berm is removed, 32 acres of prime, historic wetland habitat can be reconnected to Clear Lake and the rest of the Big Valley Wetlands shoreline.

To learn more about this wetland project and become involved with or donate to the Lake County Land Trust, visit their website here.

3. A great example of a wetland re-creation is the Tule Lake Easement Project organized and funded by Natural Resource Conservation Service or NRCS. Tule Lake is located on Scott’s Creek and highway 20, and situated between North Lakeport and Upper Lake.

This historic wetland originally took in waters from Scott’s Creek and created a vibrant and valuable wetland marsh area, surrounded by tules and other wetland vegetation, eventually allowing the water to merge into Middle Creek and out into Clear Lake through Rodman Slough.

In the early 1900’s, in order to make suitable land for growing green beans and to graze cattle, Tule Lake was drained. Later on, towards the middle of the century, levee development to the south of tule Lake, funneled Scott’s Creek straight into Middle Creek.

This channelization slowed down the flow of Scott’s Creek, causing increased flooding upstream and pushing nutrients and sediments directly into Clear Lake instead of providing an opportunity for them to slow down, settle and filter out into Tule Lake, like they had been able to for thousands of years before the conversion. The conversion of Tule Lake from a wetland might have significantly contributed to the start of degraded water quality in Clear Lake.

Luckily in 2013, a majority of the parcels of Tule Lake were purchased as part of a Conservation Easement agreement between the private landowners, the NRCS, and the US Department of Agriculture. This effort included the removal of all agriculture and grazing from the Tule Lake parcels and the re-connection of Scott’s Creek to Tule Lake through the demolition of some of the levee system along the south side of Tule Lake.

This project is still ongoing, especially in the re-establishment of tules in and around tule Lake. If you want to be involved in future volunteer efforts to replant and restore tules in Tule Lake, you can contact the local NRCS office, in Lakeport, at 707-263-4180.

4. Clark’s Island Invasive Removal and Tule Restoration Project. This project is relatively small (~1 acre) but very important for the communities in the Clear Lake Keys and Oak’s Arms of Clear Lake. This project is being organized by the County of Lake Water Resources Department and project partners and funders from County of Lake Public Services, County of Lake Department of Agriculture, the Tribal EcoResotration Alliance (TERA), Big Valley Rancheria, and Robinson Rancheria.

One of the sources of nutrients into the Oak’s Arm of Clear Lake is from the Clearlake Keys, a man-made system of channels and subdivided homes built over a converted marsh wetland in the 1960’s.

Before the subdivision was built, the marsh wetland located in the cove now covered by Clear Lake Keys, probably served to filter nutrients and sediments coming down from the Schindler Creek, from High Valley, atop the presiding hill above the Keys. This historic marsh wetland also probably provided habitat and food for Clear Lake fish, waterfowl, and animals.

The benefits of this wetland were erased when the sub division was constructed, and now the channels are susceptible to sedimentation and nutrient enrichment. Invasive plants like Creeping Water Primrose, native to South America, find the calm waters of the nutrient-rich keys a prime habitat and have grown in large abundance and thick densities throughout some of the keys.

There are lots of negative impacts from Primrose, including some public health associations with West Nile Mosquito prevalence. To learn more about Primrose, I refer you to a previous column from August 2021 “Called Peeved about Primrose.”

In 2021, The County of Lake Water Resources Department and TERA experimented with some removal techniques for primrose in the Clark’s island area of the Keys. Taking advantage of the low water levels and exposed, dry ground, the County and TERA tried out methods of manual removal, self-mulching, weed-whacking, and solarization, to control the primrose. Some methods worked better then others, but in December 2021, enough of the primrose had successfully been removed that tule replanting was possible.

This project will continue for the next few years, with ongoing primrose management and maintenance of the newly planted tules, to encourage them to establish into a health tule bed that can provide wetland benefit to the Clark’s Island area and the greater Clear Lake Keys and Oak’s Arm area of Clear Lake.

If you want to learn more about this project, or be involved, please contact Water Resources at 707-263-2344 or send an email to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Sincerely,

Lady of the Lake

Angela De Palma-Dow is a limnologist (limnology = study of fresh inland waters) who lives and works in Lake County. Born in Northern California, she has a Master of Science from Michigan State University. She is a Certified Lake Manager from the North American Lake Management Society, or NALMS, and she is the current president/chair of the California chapter of the Society for Freshwater Science. She can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?