March 16-22 is Sunshine Week, the time to discuss and explore the concept of open government. The following column, provided by Sunshineweek.org, in one of a series Lake County News will offer this week as part of the important discussion of keeping government information available to the public.

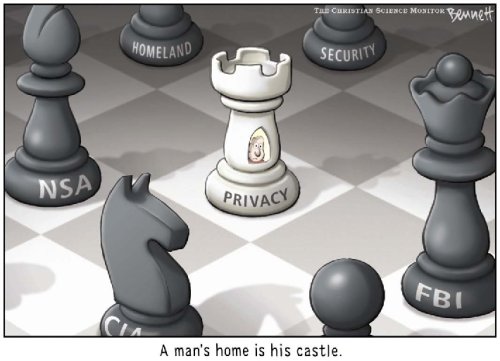

It's been a few tough years for open government in the United States. Security fears, combined with a president determined to protect his prerogatives, have kept advocates of transparency playing defense. There are signs that the tables are beginning to turn, but it's been a draining fight to maintain laws and policies built up over decades.

However, there's better news elsewhere. Since 2001, almost 30 other countries have adopted U.S.-style Freedom of Information laws, which provide citizens with a right to government documents. Among the most recent adopters are the two most populous countries on earth: India and China. The right to information, once known only to the millions living in wealthy democracies, is being extended to billions of the world's poor.

India might be the most fascinating laboratory for freedom of information in the world today. The country's center-left government adopted a national Right to Information Act soon after its election in 2004. The law is sweeping in scope: it covers not just federal agencies, but also 35 states and territories, and thousands of lower-level governments.

The media quickly began exploring the potential of the new law. Last month, the national newsmagazine India Today featured an exposé on the travel habits of the country's unusually large Cabinet that relied on documents gleaned through 60 formal requests under the new law. In total, the magazine found, 71 Cabinet ministers had logged over 10 million miles of international travel in under four years. It takes "Olympian stamina" to use the law, says editor Aroon Purie, but the results have helped to hold ministers accountable for abuse of taxpayer money.

More remarkable is the way in which disadvantaged Indians have seized on the new law to remedy grievances against local officials. In Chandrapura — a poor rural village of 2,500 in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh — citizens used the Right to Information Act to pry out information about long-promised development projects. Officials eventually relented, providing the village with access to electricity and a bridge that gives access to markets during the long rainy season.

Journalists Maneesh Pandey and Misha Singh say that Chandrapura is a "shining example" of how access to information is changing life for the poor. In Keolari, another village in Madhya Pradesh, the law was recently used to prove that a local councilor had unlawfully taken control of a well that is one of the village's only sources of water. In the Indian capital, Delhi, local groups rely on the law to expose payments to contractors for public works that were never completed. A civic organizer in Mumbai says the Right to Information Act "is like a brahmastra," a devastating weapon created by Brahma, the Hindu god of creation.

In truth, however, it's not just the law that makes a difference. It's the combination of law, a free press, and civic groups that persist despite threats and assaults. Last December, an activist in the state of Rajasthan was beaten outside a government office after making a request for documents about a local employment program. Earlier, an organizer in Delhi had her throat slit while working to extract details about food rations for the poor.

China is another intriguing testing-ground for the right to information. Major cities such as Guangzhou and Shanghai have had disclosure rules for several years. Officials in Shanghai received more than 30,000 requests from citizens in the 18 months after the adoption of their 2004 policy. One district in Shanghai actually organized a team of 300 volunteers to help citizens root information out of local offices.

Last spring, China's central government went a step further, adopting a national Freedom of Information regulation. The regulation, which goes into effect in just six weeks, will cover all levels of government, as India's law does.

A natural question is why the leaders of a one-party state would be eager to adopt a policy that is usually sold as a tool for limiting governmental power. But China's leaders have their own troubles, for which transparency seems the right prescription. The legitimacy of the entire regime is threatened by bureaucratic corruption and incompetence. The rising number of "mass group incidents" — that is, protests and riots — is one sign of growing anger over the government's inability to deal with rapid growth, urbanization, and environmental decay.

China's leaders hope that a Freedom of Information policy will provide an outlet for citizen frustration and impose discipline on lower tiers of the Chinese state. It's a paradox: a "top-down policy," as one analyst says, aimed at enlisting ordinary people to serve as watchdogs on behalf of the center.

It remains to be seen how well this policy will work. The policy applies across the largest bureaucratic complex on the planet, and there are bound to be immense challenges in assuring that lower-level officials pay attention to directions from distant Beijing. The lack of a free press, limited political rights, and a weak judiciary also complicate matters. What good is information, after all, if you lack the capacity to act on it?

Still, it is an extraordinary experiment. If Chinese and Indian policies succeed, it will be an accomplishment that dwarfs any of the transient setbacks in the United States and other western countries. Over 2 billion people — more than one third of the world's population — will see the promise of more open government.

Roberts is a professor of public administration in the Maxwell School of Syracuse University. His book, "Blacked Out: Government Secrecy in the Information Age," is published by Cambridge University Press. His Web address is http://www.aroberts.us.

{mos_sb_discuss:4}